In May 1918 Grant entered a very busy period in which he had no time to write in his journal but continued to write letters to friends and family. Censorship of his letters continued to be an annoyance, and he tried throughout the war to find ways to get his letters to their recipients without being "cut to pieces."

In this letter he tries to assuage any panic his family might have felt when they read his name on a casualty list in the newspapers.

Convois Autos.,

S.S.U. 647,

Par B.C.M.,

France.

Friday – May 24, 1918

Dear Family:-

I want to get this off by the Base Censor so will make it short and snappy and write you later at greater length. Dot tells me that one of my letters was all cut to pieces by the censor, so I’m taking no more chances.

I have already cabled you: “Don’t be alarmed at any casualty list. Am feeling fine.” You see, in a little action not long ago eight of us got a little more Boche gas than was good for us. We went to a hospital for a few days’ rest. The other day on looking through a casualty list I saw Jack Kendrick’s name and “severely wounded” after it. It frightened me somewhat because I know you see the lists and if his name appeared why not the rest of us. There were eight of us from 647 in at the same time: Kendrick, Jack Swain, Jack McEnnis, Speed Gaynor, Risley, Wallace McCrackin, Deveraux Dunlap and myself. It was nothing serious at all and hope you haven’t worried. We are all back on the job again feeling fine. It was so trivial that I had planned on saying nothing about it until I saw Kendrick’s name. Believe me when I say that we are perfectly all right again. We couldn’t help but get well in a hurry as they put us on liquid diets when none of us had eaten for two days previous. We would have starved if we hadn’t gotten well in a hurry. No more hospitals for me. It’s a good story which I hope I can tell you in another letter.

Have been getting your letters quite regularly of late. Day before yesterday I received Dad’s mailed April 22 and Marion’s of the same date and one from Johnnie. Today I got a bunch of real old mail dated back in the earlier part of March. It must be about cleared up now. I hope you have received the letters which were supposed to have reached you during that month in which you received none.

The Liberty Loan was truly a great success, wasn’t it? If Germany’s success depended along on your ability to raise money she would have been defeated long ago. But we are doing our best over here and if you should ask me for my opinion I would say that things never looked so bright for the Allies as they do right now taking everything into consideration. I wish I could go more into detail but censorship regulations forbid.

Have a call now and will mail this on my way out. Will write at greater length tomorrow if all goes well.

Love,

Grant.

Thursday, May 24, 2018

Saturday, May 19, 2018

I never saw such ghastly sights in my life as I saw that morning.

The advent of chemical weapons was one of the most vicious aspects of the First World War. While far more soldiers were killed by bullets and artillery, those that perished from poison gas died an agonizing death, sometimes weeks, months or years after the attack.

Today, nearly one hundred years later, the chemical weapons from WW I are still with us. More than a billion various kinds of artillery shells were fired in the North and East of France. And one in four did not explode. So the large number of buried shells is a problem that has lasted for a century, and will continue to be for a century more longer. In France unexploded chemical shells are discovered nearly every day, and as they age and corrode, their contents can be released with deadly results.

Between 1945 and 2000, more than 660,000 bombs, 13.5 million and 24 million mines and various unexploded shells were found, neutralized and destroyed by members of France's intrepid bomb-disposal teams. 617 of them have been killed and thousands more injured in the removal of the shells in that time.

In this diary entry, Grant Willard describes one of his horrifying encounters with chemical warfare. This one just happened to be a case of friendly fire.

Sunday, May 19, 1918:

Summer has come in earnest. No more coats (if we can help it), and no more heavy underwear (if we could possibly get a hold of something light). France is perfectly glorious in such weather.

We are still with the 26th doing the same work as before. Nothing much of excitement has happened since the Seicheprey experience. We have been putting in its work since we left the hospital. Kendrick still has a cough and his burns troubled him for a long time. Risley’s eyes have bothered him ever since. The sun hurts them. Gaynor’s throat still bothers him. A week after we were discharged from the hospital I took a bath. About an hour afterward I began breaking out in the most painful way. They said it was gas and gave me a solution of something to wash in. It helped some, but I am still pretty sore in some places.

We are still with the 26th doing the same work as before. Nothing much of excitement has happened since the Seicheprey experience. We have been putting in its work since we left the hospital. Kendrick still has a cough and his burns troubled him for a long time. Risley’s eyes have bothered him ever since. The sun hurts them. Gaynor’s throat still bothers him. A week after we were discharged from the hospital I took a bath. About an hour afterward I began breaking out in the most painful way. They said it was gas and gave me a solution of something to wash in. It helped some, but I am still pretty sore in some places.

We were sent back on duty, after returning from Ménil-la-Tour two weeks ago, on May 9. Swain, Dunlap and I went to Commanderie and Hap and McCrackin went to Gironville[-sous-les-Côtés]. The first day was very quiet. We work on 48 hour shifts at these posts. At Commanderie we live in a two room abri doing our own cooking. We always have a good time up at these posts because there are no officers, except the French who are very nice with us, and we are our own bosses. The work is light as a rule; we make but two posts--Ranval and St. Agnant[-sous-les-Côtes] (the latter is supposed to be a night post, being within ½ km of the front line, but we have often made it in daytime).

On the 2nd night we were told to be ready for an attack in the St. Agnant sector. Maybe the Boche heard about it too, maybe it was accidental. The attack was set for 4 A.M. the following morning. The Boche sent over much gas at 2 A.M. with terrific results on the Americans. We were all called out at 3 A.M. and we kept very busy carrying gas patients all through the attack. The French made the attack, but the American boys suffered.

I never saw such ghastly sights in my life as I saw that morning. Boys apparently alright to start back to the hospital with a little gas would die while you were trying to load them into your car. I watched three boys pass off thusly and felt so faint and sick I could see no more and retired to an abri while they loaded my car. I talked with one boy who was sitting up on his stretcher waiting to be loaded into my car. His name was “Schmittie” and a great favorite among his friends. He said they were taken by surprise and that a gas shell had exploded at the door of their dug-out and hadn’t wakened them. 19 in that one dug-out were gassed. He asked which car he was going down in and was advised to lie down and be quiet. Ten minutes later he was dead. Apparently no suffering except a cough. That was enough for me. We worked all through the day and late into the night carrying gas patients. The attack was a success bringing in 100 prisoners and destroying many Boche front line fortifications. My aide was in bed for four days with a gas cough and stomach trouble. Must have gotten it off of the clothes of patients.

One other gas attack, one turn at Gironville were all that happened after that. We had a pretty good rest in all. We swim in the Meuse now, walk into Commercy and around the surrounding country. The Lieutenant is feeling pretty good these days. He expects another ten days will find us in Nancy getting our cars painted the French grey ready to join a French division. Here’s hoping!

Today, nearly one hundred years later, the chemical weapons from WW I are still with us. More than a billion various kinds of artillery shells were fired in the North and East of France. And one in four did not explode. So the large number of buried shells is a problem that has lasted for a century, and will continue to be for a century more longer. In France unexploded chemical shells are discovered nearly every day, and as they age and corrode, their contents can be released with deadly results.

Between 1945 and 2000, more than 660,000 bombs, 13.5 million and 24 million mines and various unexploded shells were found, neutralized and destroyed by members of France's intrepid bomb-disposal teams. 617 of them have been killed and thousands more injured in the removal of the shells in that time.

In this diary entry, Grant Willard describes one of his horrifying encounters with chemical warfare. This one just happened to be a case of friendly fire.

Summer has come in earnest. No more coats (if we can help it), and no more heavy underwear (if we could possibly get a hold of something light). France is perfectly glorious in such weather.

We are still with the 26th doing the same work as before. Nothing much of excitement has happened since the Seicheprey experience. We have been putting in its work since we left the hospital. Kendrick still has a cough and his burns troubled him for a long time. Risley’s eyes have bothered him ever since. The sun hurts them. Gaynor’s throat still bothers him. A week after we were discharged from the hospital I took a bath. About an hour afterward I began breaking out in the most painful way. They said it was gas and gave me a solution of something to wash in. It helped some, but I am still pretty sore in some places.

We are still with the 26th doing the same work as before. Nothing much of excitement has happened since the Seicheprey experience. We have been putting in its work since we left the hospital. Kendrick still has a cough and his burns troubled him for a long time. Risley’s eyes have bothered him ever since. The sun hurts them. Gaynor’s throat still bothers him. A week after we were discharged from the hospital I took a bath. About an hour afterward I began breaking out in the most painful way. They said it was gas and gave me a solution of something to wash in. It helped some, but I am still pretty sore in some places.We were sent back on duty, after returning from Ménil-la-Tour two weeks ago, on May 9. Swain, Dunlap and I went to Commanderie and Hap and McCrackin went to Gironville[-sous-les-Côtés]. The first day was very quiet. We work on 48 hour shifts at these posts. At Commanderie we live in a two room abri doing our own cooking. We always have a good time up at these posts because there are no officers, except the French who are very nice with us, and we are our own bosses. The work is light as a rule; we make but two posts--Ranval and St. Agnant[-sous-les-Côtes] (the latter is supposed to be a night post, being within ½ km of the front line, but we have often made it in daytime).

On the 2nd night we were told to be ready for an attack in the St. Agnant sector. Maybe the Boche heard about it too, maybe it was accidental. The attack was set for 4 A.M. the following morning. The Boche sent over much gas at 2 A.M. with terrific results on the Americans. We were all called out at 3 A.M. and we kept very busy carrying gas patients all through the attack. The French made the attack, but the American boys suffered.

|

| Canadian soldier with gas burns. |

One other gas attack, one turn at Gironville were all that happened after that. We had a pretty good rest in all. We swim in the Meuse now, walk into Commercy and around the surrounding country. The Lieutenant is feeling pretty good these days. He expects another ten days will find us in Nancy getting our cars painted the French grey ready to join a French division. Here’s hoping!

Saturday, May 12, 2018

Every day is Mothers’ Day with me.

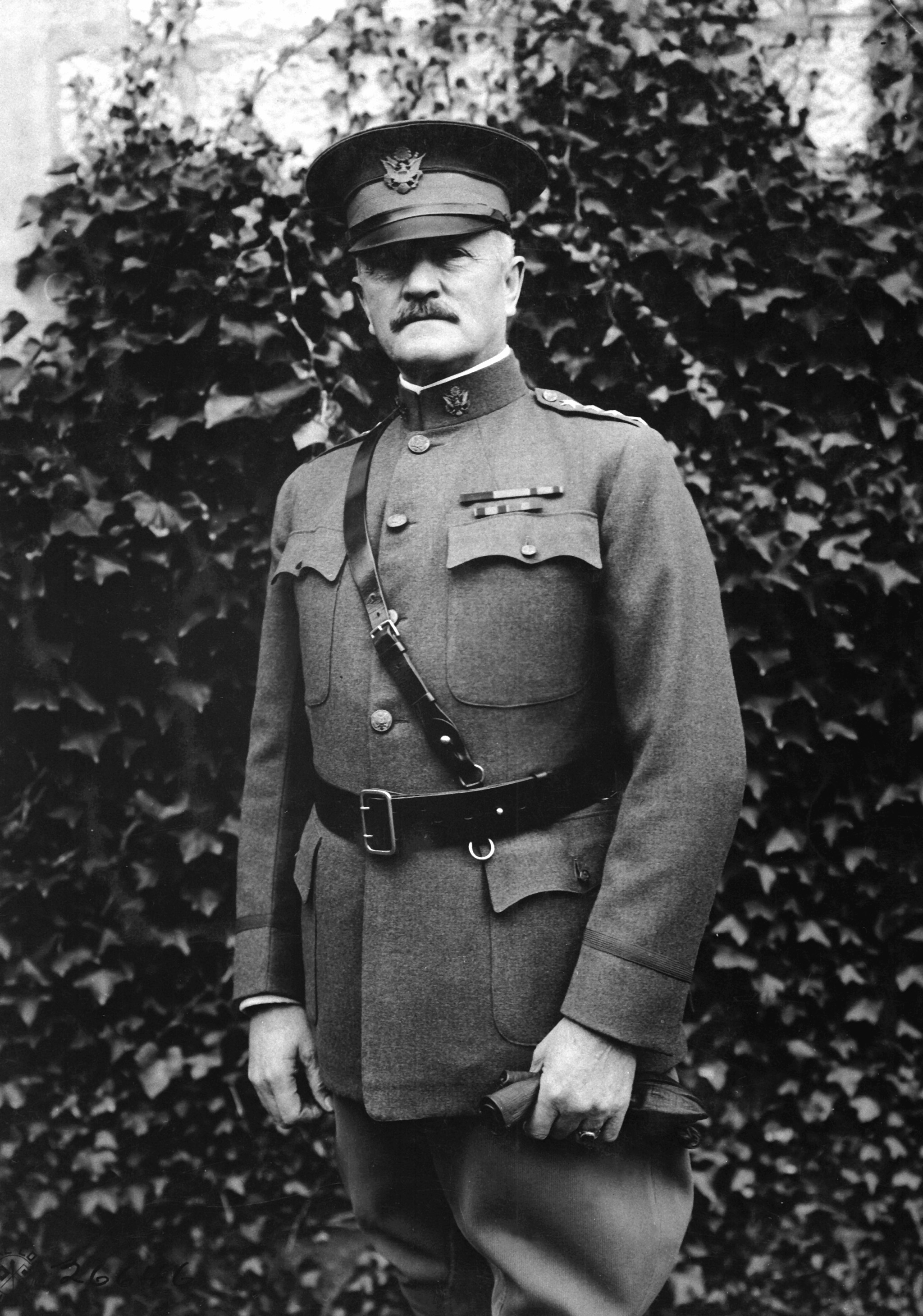

John Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948) was the United States Army general who led the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I. Owing to a request from General Pershing, Grant wrote his mother a very interesting and descriptive letter just a few days after he'd last written her.

Sunday – May 12, 1918

Dear Mother:-

|

| John J. Pershing (1860-1948) |

One year ago today Dot and I were pacing the Board Walk at Atlantic City, N.J. About this time (10 A.M.) I had bought her a bouquet of lily-of-the-valley and I myself was wearing a white carnation. Those were surely happy days. After our promenade we sat down to a table with white table cloth and napkins and ate a delicious chicken dinner. Will those good times ever return? Yes, surely they will. Even better days are in store for us all after this long period of privations has terminated.

It’s a typical American May day direct from Minnesota today. The sky is cloudy and threatening. The river is swelled with recent rains. The hills are a brilliant green with very heavy foliage. This is the most beautiful post of any on the two fronts we are covering. These are seven of us up here at present-–three of our cars and one French ambulance which takes care of the French wounded in this sector. We are now driving with our own aides so we are a very happy party indeed.

We are living in a two-room, corrugated steel abri well protected with logs and stones. The back room is our sleeping room where the seven of us sleep on stretchers arranged on racks of two layers. (I have an upper.) The front room is our sitting room, dining room, kitchen and library. It is now being used for all purposes at once. Hap and I are writing on the tables. Titchener (son of the famous psychologist) is reading; Woodie is munching crackers; the Frenchman (a very nice young fellow who has been several times wounded so that it is necessary for him to be in some non-combatant branch of the service) is preparing our noon meal on a stove which some ingenious hand has made from a gasoline “bidon” [gas can]. Judging from the smell I should say that he is preparing a tasty “slum-guillion” with onions in it. The other two boys are off on a call. McCrackin, “the Montana banker” (Hamilton, Montana) is driving the car with Bert (ex-instructor of French in eastern public schools) as his aide.

As I sit here writing I can look out over a beautiful valley in the middle of which sits a chateau enclosed with an eight foot stone wall now pierced with many shell holes. On the hillside across the valley is a quarry where men in uniform work all day long extracting the soft stone for road building. Today, being Sunday, everything is quiet except the wind which toils on continuously, never resting. One would little suspect that these roads and valleys are a veritable nest of batteries but so it proved when, last week, there was “something doing” up here. The French are very clever at hiding their positions. I was driving along a piece of road the other day over which I had driven many times before, never suspecting that there was such a thing as a gun in the vicinity. Bang! Bang! Bang! Went a battery of “heavies” right beside me. My “Henry” didn’t like it very well and tried to shin a tree. After enticing it back into the road I tried to locate the battery but I couldn’t see a sign of it. It was two days later, after the positions had been changed, that I discovered they had been within 20 yards of the road. This just goes to show how cleverly the Frenchmen had done their work. I wish they would blow a whistle or something to warn the ignorant ambulance driver. They’d like to scare the liver out of a man.

Last week we had considerable work to do in this sector and for 48 hours none of us had a chance to sleep but it has again quieted down. We have been up here today since 8 o’clock this morning and have had but one call.

Since last writing you I have received several letters and packages. Your letter of April 3 from Long Beach, Tib’s of the same date, Dad’s mailed Apr. 8 enclosing Liberty Loan “dope,” a card from the Sperrys, a couple from Dot. Also a sweater, socks, air-pillow, photographs, a book and a comfort kit from Dot. Two Literary Digests also arrived. All were very welcome. The packages Dot sent over by Agnes Nicholson and were mailed to me from Paris.

|

| Louise R. Willard (1867-1940) |

The only thing I can think of now that I want next to a declaration of peace is some paper for a No. 509 loose-leaf I-P notebook. I enclose a sample of the kind I would like. I asked for this once before but I guess you never got the letter.

With much love to all,

Grant.

Sunday, May 6, 2018

By May 1918, Grant Willard had been away from home for a year. The only "family" he had near him were the members of SSU 647, and the makeup of that unit was markedly different than that of Norton-Harjes 61 the year before. 647 was an U.S. Army unit containing men from different walks of life. Some were, of course, the well-educated sons of privilege--the "gentlemen volunteers"--with whom he'd volunteered in the Norton-Harjes unit. But in this new unit Grant was rubbing shoulders with men from the East, Midwest and South whose backgrounds and experiences were far different from his own.

On this day in 1918, Grant wrote his mother, Louise, a candid letter describing his comrades. Part of this letter was censored or Grant used a code so as not to divulge the true names of the French villages were he was serving.

On this day in 1918, Grant wrote his mother, Louise, a candid letter describing his comrades. Part of this letter was censored or Grant used a code so as not to divulge the true names of the French villages were he was serving.

Convois Autos.,

S.S.U. 647,

Par B.C.M.,

France.

Monday – May 6, 1918

Dear Mother:-

You know, we have a very cosmopolitan outfit in #647. It wasn’t so noticeable until we fell in with the various American units which were all organized from some definite state or group of states. The question is frequently asked, “What part of the States do you fellows come from?”

Where upon we have to recite the history of #647:

|

| SSU 647's insignia |

Leo McGuire claims Oklahoma as his home. He is part Indian which shows in his skin. He is a great favorite among the fellows though he is very quiet except on certain occasions when he is the nucleus of the whole party. Mac has been very quiet and sober of late and isn’t quite himself. You see, the Boche shot his car out from under him the other day with a 77 and Mac had to carry his orderly to a place of safety where they were later picked up by another of our cars. The orderly is still in the hospital but Mac refused to go even to rest up awhile. He was all for going back and salvaging his car until the Lieutenant flatly refused to allow a man to go close to it. Neither man was badly hurt – just nerves, you know. I passed the car the other night about dusk and though you can be I wasn’t wasting any time on the road I had a good look at the ruins. I pronounce it a miracle that either boy came out alive. Now don’t let this worry you a bit because we are no longer allowed to make this post in the day time and it is perfectly safe after dark.

+Snader+with+a+case+of+roast+beef.jpg) |

| Snader with a case of roast beef |

From the southern states we have “Woodie” Woodell, Jack Swain, Deveraux Dunlap and Tod Gillette--four mighty well-liked boys. Woodie and Tod come from Florida while Jack and Dev are only too proud to boast of Dallas, Texas. These four all talk with the southern dialect and stick together like brothers. Anyone of them will give you half and more if you would take it, of anything they own. Woodie was manager of a steam laundry before coming to “do battle,” as he says. While at training camp he became bored with doing just what the others did and no more so he went into the kitchen and is now a 1st class cook. He’s ashamed of his position and is so afraid that someone back in the States will get a hold of it that he gets terribly blue whenever he thinks of it. He can’t get rid of his cook’s job because he’s too good at it. Tod was manager of an artificial Florida ice plant when he too a sudden dislike to the Boche and left within a week’s notice. Dev. and Jack are from Sewanee College of the South and were in an officers’ training camp when they decided that it was too slow getting to France that way so they resigned and volunteered with the Norton-Harjes unit.

Jack Kendrick our 2nd Sergeant is a Connecticut boy. His family was at one time very wealthy but suddenly went to pieces financially causing his father’s death and leaving Jack a mother and sister to take care of. He did it so admirably through the automobile business which he built up that he was able to come to France 3 years ago with the Norton-Harjes unit and has been over here ever since. He is a nervous, overgrown kid who talks and stutters so fast you can hardly understand him. He’s afraid of nothing except that someone in the section is going to have a little excitement which he can’t share. When we are doing front work he is never at the base post where he belongs but can always be found at the most advanced position seeing that everything runs smoothly. The Frenchmen think the world of Jack and as to the feeling of the section is would be putting it mildly to say that there is no officer in our section, commissioned or non-commissioned, from whom, we had rather take orders than Jack.

Then there is Pinky Harris, New York, about 30 years of age who has seen a great deal of life and can speak Kipling by the yard. We also have six men from Clark’s College in Worchester--everyone a good scout. And one could go on describing every man in the section ending up with the same phrase--“he is a good scout.” There is not a man in the outfit whom you would be ashamed of in your own home. We’ve had nothing but perfect accord since we have been together.

We are pretty well split up as we are here for the purpose of helping out other Ambulance companies. Ten of our cars are working in one sector with one company and five in another with another. Five cars are kept idle. Our system of shift (rather intricate) is this: our base past is at V[ignot] where five cars are kept idle. At M[andres-aux-Quatre-Tours], some distance off, we have a base for ten cars which work together. From this base five cars go to A[nsauville] for 24 hours. From

A[nsauville] two cars are sent further up to B[eaumont]. When one of these cars gets a call it stops at

A[nsauville] on the way back to the hospital and sends another car up to take his place at

B[eaumont] and when he returns from the hospital he parks at

A[nsauville] . In this way everybody is subject to the same calls and everybody has an equal chance. Morning and night the 24 hour shifts are made – 2 and 3 cars respectively. I am at base

M[andres-aux-Quatre-Tours] now and go on every night for my 24 hours. Hap is up here with me but goes on in the evening and I don’t see much of him. Sometimes I find myself making my bed beside him but when I wake up it is either because I have a call or because it’s morning and Hap has gone out on call. Tomorrow our 7 days is up and return to

V[ignot]. The other sector is worked with

V[ignot] as the base and five cars stay on posts 48 hours after which time they return to

V[ignot] and the five idle cars go on. Though this system may seem intricate on paper it is really very simple and satisfactory. We are on the move practically all the time. The other Ambulance Cos. have gradually withdrawn to rear work in order to give them a chance to overhaul their much overworked cars.

We have had a comparatively easy time of it up here on this sector. Two weeks ago there was considerable excitement here and every car was busy for two days but everything is serene again.

In many ways I am mighty glad to have had this chance of working with the boys from across the sea though we are only loaned to them. When this division is withdrawn we don’t know what will become of us. Perhaps we will go with them. They are a fine bunch of boys and great fighters. Most of them come from the eastern states. Haven’t met a soul among them I know but there must be some. Weiderman’s company is not attached to this division though they happen to be here at present.

Will finish this after supper before I go on duty and mail it here. Our Lieut. won’t censor this letter. There is another way.

7 P.M. Sargent Kendrick just came in to say that we would be relieved at 8 A.M. tomorrow so we will stay in here tonight which gives me more time in which to finish this letter.

We ate what we called “slum gullion” for dinner tonight. It’s nothing more nor less than a stew consisting of meat, potatoes, tomatoes and whatever else they may have lying around the kitchen – on toast. We have coffee three times a day with milk when there is any. Tonight we have dates for dessert. This ambulance company feeds very well.

Got a letter from Bill Everett the other day. I hope we can meet though I don’t see how except by chance. He may be right near me and I now know anything about it except by a chance meeting. Isn’t that a sad state of affairs?

Mother, the prospect of us all being reunited soon doesn’t look very promising, does it? A year ago at this time I had left you and was on my way to say good-bye to a very dear little girl in Pennsylvania. Though it seems far more than a year since that time things have cleared up a lot for me. She is a dear, isn’t she, Mother? You know it now perhaps as well as I do. Perhaps better than I do with your superior experience. But I feel far better now than I did then. I am surer of my ground. I’m surer of her. I don’t think any longer – I know. But I have been awfully foolish in a great many ways. I’m afraid I have hurt Mrs. Houghton pretty deeply and now, as I look back on it, I can see how and why. My problem now is to make good to her. I no longer want Dot over here with me but want her right in Ambler with her mother and moreover I want her to look at this whole thing more in the way Marion is looking at it. How can I make her happy to stay and do as her mother wants her to do? That’s my problem now.

Well, I must quit now and read the evening papers--Daily Mail, New York Herald, and Tribune.

Much love to all,

Grant.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

+with+647+insignia.jpg)